Gregory Betts reviews David Shield’s Reality Hunger

Gregory Betts reviews David Shield’s Reality Hunger

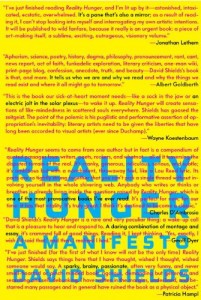

Reality Hunger: A Manifesto

David Shields

Knopf, 2010

240 pages, $24.95

“89: If my forgeries are hung long enough in the museum, they become real.”

David Shields — prize-winning author and almost New York Times bestseller — has a new book out that contemporary prose writers would be well advised to consult, if only to surrender themselves to an onslaught of insight into and provocations concerning what and why we write (regardless of whether it be labelled fiction or non-fiction). The book regularly returns to its central premise that the generic categories of prose are actually and fundamentally arbitrary and misleading, especially in this the memoir (or life-writing, as we call it here) age. As he writes, “149: All the best stories are true.” Fiction and non-fiction are the same.

Lacking no lack of ambition, Shields’ Reality Hunger (Knopf, 2010) purports to unify and inspire a generation of new novel writers: “My intent is to write the ars poetica for a burgeoning group of interrelated (but unconnected) artists.” He didn’t ask me, however, and the title after the colon reads somewhat baldly: “a manifesto.” If he had asked, I would have suggested a subtitle something along the lines of “Writing in the Simulacra” or perhaps even “A Manifestation.” To be clear, the book is mislabelled: it is not a manifesto. Reality Hunger presents a collection of 617 numbered aphorisms, epigraphs, plagiarisms and observations about the relationship between post-industrial revolution literature and the contemporary media moment. The vast majority of the book is made up of quotes — quotes that are, to the author’s confessed regret, catalogued and (poorly, haphazardly) cited at the back of the book. For most of the book, you do not know who is responsible for the words you are reading. And therein dwells the book’s greatest pleasure: the creation of a sustained authorial voice through other voices.

I have seen less ambitious versions of this kind of experiment before. In the 1940s and early 1950s, Bertram Brooker wrote an enormous tome of essays that sits unpublished in the University of Manitoba Archives and that attempts to engage with the philosophical tradition almost entirely through quotation. Appropriately, the essays are collected under the title The Brave Voices. The point he makes (which he makes more subtly in his novels as well, arguably more forcefully) is that literature distorts one’s relationship to the “real” (in Brooker’s vocabulary, the “vital”) and that all books, in any case, come from previous books as opposed to life. Get back to real life, Brooker instructs: “The goal is to raise oneself almost to the point of pure energy — the rushing redness of blood.” Shields echoes: “544: Write yourself naked, from exile, and in blood.”

Benjamin’s Arcades Project (cited in Shields’ book) is a more iconic example of a meta-conscious text that undermines the singularity, linearity and the fixity of the author’s voice. James Joyce, too, can be connected to this collage-quote-text tradition. He himself once quipped, “I am quite content to go down to posterity as a scissors-and-paste man” (I just plagiarized Shields by stealing his citation of Joyce, though the Joyce is itself a stolen good).

Why is this remarkably innovative text not a manifesto? Through all the allusions throughout the book Shields does not propose a radical departure from well-established writing modes, nor attempt to create the possibility of a new school of writing (or even new direction). The authors he cites, from Joyce on down, before and after, create the distinct impression that Shields’ aesthetic is shared and shared broadly among many of the most canonized authors in the Western tradition. A manifesto is a propositional document, an antagonistic proposal for a new mode of aesthetical creation. Postmodern authors (especially experimental authors like Steve McCaffery and bpNichol and theorists like Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault) have long challenged the illusion of creativity and newness that modernist modes (including the manifesto) relied upon.

Furthermore, one can argue that earlier writers anticipated your movement (as Breton did of the Marquis de Sade, for instance), but it contradicts the function of the manifesto to claim that previous writers have been defining and practicing your proposed aesthetic for hundreds of years. In that case, nothing is being proposed except a reminder of the significance of enormously important previous work by other authors. Why, then, if the aesthetic is aimed at contesting the illusion of novelty (as well as the illusion of singularity, objectivism and so on), present this book through the tired, modernist rhetoric of newness? Can quoting old and canonized authors ever really amount to taking “an audacious stance,” as the copy-text purports? Does a book of quotations (distorted and arranged as they might be) really present “a ‘Make it New’ for a new century,” as J. M. Coetzee suggests? Coetzee’s praise, in fact, carries a hint of the book’s regurgitated novelty. This, of course, is the radical point Shields’ book advocates.

No manifesto then, the book in fact functions as a program for a post-realist school of fiction, carefully and thoughtfully elucidating the reasons why authors have turned away from stability in writing and from the illusion of realism (including non-fiction and realism, as they are conventionally understood). What specific stabilizing features does Shields argue need be re-challenged? Everything that continues to define and delimit any prose genre despite centuries of literary experimentation: plot, character, coherency, factuality, unity and, of course, authorship. He writes, “419: When we are not sure, we are alive.” In this advocacy, he convinces precisely by the sheer volume of authors cited, all of whom seem to speak with one voice in favour of his paradoxical rejection and embrace of realism. It is one thing to dismiss David Shields. It is another to dismiss David Shields and James Joyce. But it is but a far more daunting prospect to dismiss David Shields allied with James Joyce, T. S. Eliot, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Walter Benjamin, William Gass, Charles Simic, Philip Roth, Herman Melville, William Gibson, Douglas Coupland, Ernest Hemingway, Thomas Pynchon, Frank O’Hara, Robert Lowell, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Lionel Trilling, Emily Dickinson, Irving Babbitt, Pablo Picasso, Gertrude Stein and on and on. It is not that all of these writers agree or would have agreed with Shields in toto, but the impact of Shields’ methodical quotation system is to create the impression that the work of each embodies an essential piece in his puzzle — that his theory is the synthesis of their aesthetical accomplishments.

The book will likely be widely discussed, and deserves its attention. Few books have managed to sustain the borderblur between so many voices: it is a significant accomplishment. It makes the forceful point that we work and write and live within a system — a closed system of language, of literary conventions and arbitrary delineations that almost all of us passively accept unconsciously. The book collects half a thousand aphorisms against this passivity (some are groan-inducing and Hallmarkian, others profound and developed) — attempting to use these fragments to ruin the shores of our time. For all of our radical poetics, our experimentalisms and conceptualisms, authors have been wrestling with these same essential questions for far longer than most brave authors today would dare concede.

Gregory Betts is the author of If Language (BookThug) and The Others Raisd in Me (Pedlar Press). He lives in St. Catharines, Ontario, where he curates the Grey Borders Reading Series and co-edits PRECIPICe literary magazine.