by Amy Lavender Harris

by Amy Lavender Harris

Things float into your head when you write. Words lodge there; ideas, images, whole paragraphs coming to rest the way driftwood accumulates at the lake edge after a storm. With the right collection of words you can create structures solid enough to dwell in. You can invent people to live in them, and communities for them to inhabit. You can imagine an entire city.

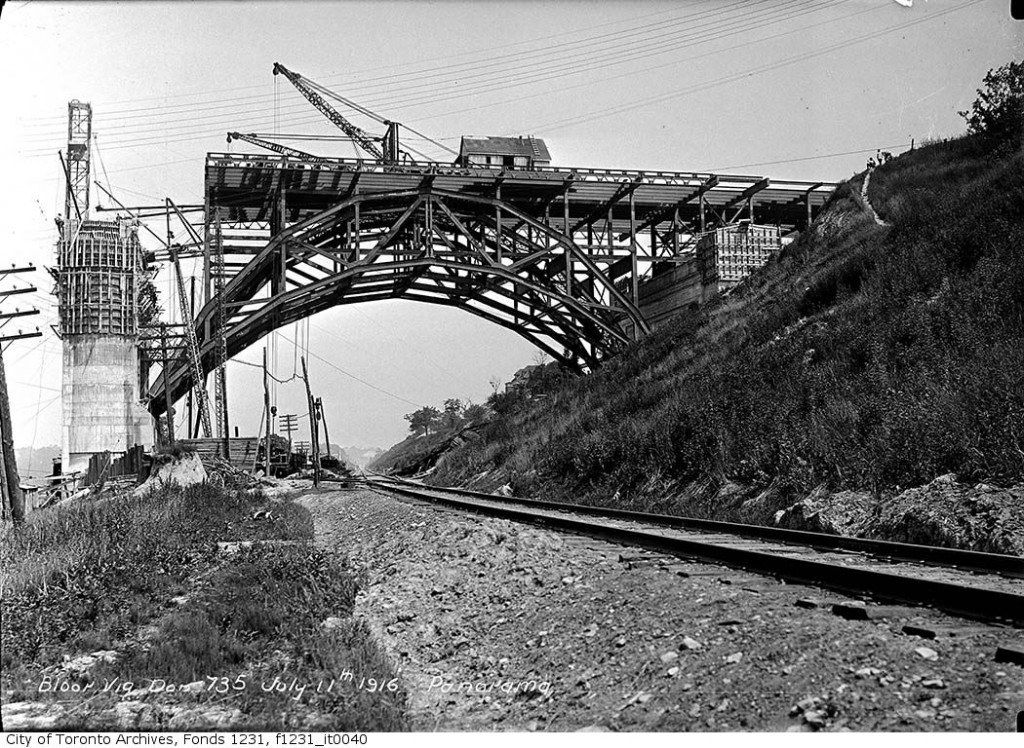

Nearly three years ago I knelt at the shore of Lake Ontario and began to gather up pieces of Toronto for a book about how the city is imagined. I stood in the shadow of the CN Tower and saw, as if for the first time, how it marks the place where the real and imagined cities meet, the origin point where the city’s coordinates resolve to zero. I crept down the long wooden staircase below the Bloor Viaduct and saw how the great bridge knits the sides of the valley together, reconciling Toronto’s present with its past and the city’s culture with its more primal nature. I learned to see the city as a place filled with stories that have accumulated in fragments between the aggressive thrust of its downtown towers and the primordial dream of the city’s ravines.

The Imagining Toronto project began at a time when commentators insisted that Toronto did not have a literature of its own. One wrote that “Toronto is not a city that lives in the imagination”; another averred that “our city awaits its great novelist”; a Toronto author suggested that “there’s a reluctance in our fiction to engage Toronto directly as a place.” Where critics did acknowledge the existence of Toronto literature, they tended to cite the same short list of half a dozen well-known authors: Margaret Atwood, Michael Ondaatje (whose only novel engaging with Toronto has become the city’s most iconic text), and a revolving selection of other writers including Morley Callaghan, Hugh Garner, Dennis Lee, and Anne Michaels.

I thought at the time that it might be possible to ferret out 20 or 30 additional novels and some poems about the city. I dug into boxes at book sales, typed “Toronto” into literary search engines, and browsed alphabetized rows of Canadian literature at bookstores, looking for stories that mentioned Toronto. I bought these books and brought them home to arrange on a single shelf in my study, a tiny converted sunroom at the back of our Toronto home.

Three years later, my little office is wall-to-wall Toronto literature and the structure sags with the weight of hundreds of novels, story collections, poetry anthologies, broadsides, and memoirs, all engaging with Toronto. Booksellers smile when they see me, anticipating watching me lurch out clutching another bundle of books, eyes glazed and wallet empty. For three years I have read nothing but Toronto literature, and for the past two years I have written about almost nothing else.

Here, as a sort of preview of the book itself, are some of the insights that have floated in from the lake edge.

First, the sheer volume of literature engaging with Toronto belies claims that Toronto is a city that does not live in the imagination. Literary works dating to the 1790s describe Toronto from the perspective of its European colonizers, and by the 1831 publication of John Galt’s frontier novel, Bogle Corbet, Toronto was making regular appearances in print. Some of Toronto’s best known literary exports — among them Ernest Thompson Seton, described by literary scholar Germaine Warkentin as the first writer to make the life of the ravines his subject in Wild Animals I Have Known, and Morley Callaghan, whose 1928 novel, Strange Fugitive, is considered the prototype gangster novel — set much of their work in Toronto. By the late 1960s, Toronto was well-known for producing provocative fictions engaging with issues of race, class, gender, and sexuality, supported by a rapidly expanding network of large and small presses. Toronto writers regularly win prestigious literary awards and their works are popular globally in translated editions, indicating that Toronto manages to play itself even on the international literary stage.

Second, the literature suggests that Toronto is a perennially emergent city in search of its own creation myths. Gwendolyn MacEwen sought to create one such mythology, inventing a protagonist called Noman, who emerges lost and amnesic from the Ontario wilderness and hitchhikes to Toronto to search for his identity. Other writers have taken up the same challenge, including bpNichol, whose Martyrology sequence describes the city rising above the ancient lakebed, its topography a metaphor for classical voyages and its streets named after saints. Maggie Helwig has taken this mythology further in her poetry and her recent novel, Girls Fall Down, relying on the city’s homeless outcasts to tell truths the rest of the city is reluctant to hear.

Third, Toronto writers engage meaningfully with what geographer Michael Doucet calls Toronto’s most prominent urban legend: the belief that the United Nations has declared Toronto the most multicultural city in the world. The myth of the multicultural city has penetrated deeply into the popular consciousness, largely because — as Doucet is careful to point out — Toronto is by any measure one of the world’s most culturally diverse cities. But Toronto writers do not deal with culture only through shallow celebrations of culture that cultural theorist Stanley Fish derides as “boutique multiculturalism.” Rather, by tackling the difficult subjects of identity and race, Toronto writers — chief among them David Chariandy (Soucouyant), Lien Chao (The Chinese Knot), M. G. Vassanji (No New

Land), and Austin Clarke (More) — encourage us to explore how we can live together, or whether we can do so at all. In doing so, they fulfill Toronto author Dionne Brand’s observation that “the literature is still catching up with the city, with its new stories.”

Amy Lavender Harris is the author of Imagining Toronto, forthcoming from Mansfield in the fall of 2009. The Imagining Toronto website — which includes a regularly expanding library of Toronto literature — is accessible at http://www.imaginingtoronto.com.